The Night Depends On How Gently We Live Beneath It

“The smallest gesture can widen the path for another life”

Each October and November, as millions of migratory birds pass quietly through our night skies, I am reminded to turn off a few more lights. What seems a small gesture, dimming our windows and gardens, is an act of care. Across the country, organizations like the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and BirdCast, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s real-time migration tracker, remind us that fall migration is underway and that artificial light confuses nocturnal travelers, leading to collisions, exhaustion, and disorientation.

The Lights Out program from the National Audubon Society expands this call to action, urging residents and cities to reduce nighttime lighting during peak migration months. It is a simple way to save lives, protect biodiversity, and reconnect with the beauty of natural darkness. This is a season to let the night work as nature intended.

My connection to birds began on the eastern end of Long Island, where ocean breezes met the marsh and the rhythm of life moved with wings. I remember the first robin’s egg, that perfect and impossible blue. I remember hatchlings being fed, the wonder of small wings testing air for the first time, and the soft thump of a bird flying into a window. Dismay has its own sound, one I have never forgotten.

With the gaze at birds from windows, memories run deep. My mother’s mother, Rose, lived with us on the same property. A small ranch cottage had been moved to the rear of our acre lot in the 1960s for my grandmother. Of Czechoslovakian descent, Rose raised my mother Dyan and nine other children on a farm in northeastern Connecticut. My grandfather, whom I never met, died before I was born.

Dear Rose would visit the main house on our property in the village of Southampton, New York, back when it was still a quiet local town most months of the year. The affluent “city people” would come out to open their “cottages” in spring, as the term went. The “estate section,” we called it. Today, the Hamptons is much different and, yes, a bit showier, though part of me still smiles at the pizazz. For locals like us, it was all an act we clued into long ago, the summer dialogue of attitude versus gratitude.

For me, even then, it was all about curiosity, seeing and learning from whomever I met, as it is today.

Grandma Rose would stroll from her cottage to our house more often in the winter, settling into a cozy corner of the kitchen that faced a large leafless viburnum bush across our driveway. A birdfeeder hung there, perfectly placed for viewing. Rose would chat with Mom and gaze for hours out that window. She knew the names of many of the birds.

My brother Chris, quiet and observant, would join me in listening. Birds remain a shared fascination between us. Chris and I are both devoted gardeners and naturalists. Now a respected landscaper and horticulturist in the Hamptons, he is never without binoculars, always ready to spot an unfamiliar duck or trace a sweet, unknown chirp.

Those quiet mornings beside Rose’s window, with Chris listening nearby, were the first moments I understood that tending to life, birds, gardens, even a patch of winter light, was its own form of devotion.

They Believed the Garden Could Hold Every Kind of Truth

“I listened to the ladies, and the trees listened too.”

It was my mother’s friend, Charlotte Cord, who first called me Keeper of the Birds. She lived on Ox Pasture Road in Southampton, surrounded by clipped hedges, generous gardens, and tall old trees. Charlotte was wealthy, but in the garden never carried weight. The Hamptons could be a place of social tiers, yet the garden leveled everyone. Gardeners, neighbors, and old friends shared the same shade and the same attention to what was living and growing.

When my mother and Charlotte were together outdoors, their friendship had a calm ease. They exchanged cuttings and clippings, waited for the first bloom, and spoke of trees as though they were old companions. I grew up inside that quiet devotion, learning that care is practiced in small, steady gestures, often with soil under the nails and silence as its reward.

The canopy above them was a kind of truth. It taught that all care begins with attention. And I listened to the ladies.

That is what remains with me: care as belief, as presence, as the simple act of noticing.

Each winter, Charlotte and her husband Orlando went to Longboat Key on Florida’s Gulf Coast, leaving me to feed the birds and the squirrels who lived there year-round. Some of the birds migrated south, but others stayed, as if the garden belonged to them too.

Before school, I pedaled my red three-speed Schwinn bicycle two miles through the quiet village to their estate. In Charlotte’s garage stood tall aluminum cans filled with thistle, sunflower, and wild birdseed. I filled the feeders, scattered peanuts on a small wooden platform she had built for the squirrels, and watched the morning unfold. Goldfinches, juncos, sparrows, and chickadees fluttered in, joined by a few striking white fantail pigeons from a nearby property.

They were beautiful yet vulnerable, and even then, I understood that beauty can carry its own risk. Camouflage, I realized, is nature’s version of fashion, a kind of visual safety. Looking at those pigeons, I saw something both innocent and radiant, but also exposed. Out in the wooded areas, those white-winged angels would be fair game for predators. And indeed, red foxes still wander those neighborhoods, or “sections,” as some locals like to say.

“Some of our earliest lessons in care come disguised as chores”

Another task carried its own excitement: tending to Charlotte’s gold 1970s Cadillac Coupe DeVille with the black landau roof. The car, a heavy creature of beauty and bravado, had a quiet confidence I admired. While others in the neighborhood drifted by in Mercedes or the occasional Bentley, the Cadillac seemed to carry a kind of wise American dignity. I liked it then. I still do, if they all become eco-vehicles.

My job was to start the engine each week, to keep the motor alive inside that gleaming 4,650-pound body of prestige. In the small garage, the smell of gasoline rose as the engine rumbled awake, my first sharp encounter with fossil fuel, strangely mixed with the soft scent of birdseed stored nearby.

Looking back now, that pairing feels almost prophetic, the sweetness of care beside the shadow of harm, a quiet foreshadowing of the themes that run through my art today.

The Art of Noticing

“Every hum, every flicker, every wingbeat, another way the world reveals itself”

The car fascinated me. It had electric windows, my first glimpse of a small modern luxury, and I was entranced by the gentle hum as the glass glided up and down at the touch of a button. I took “keep it running” to mean giving the Cadillac a little exercise, guiding it slowly up and down the long, hedge-lined drive without anyone knowing. Most visits were in the morning, though sometimes after school, when in winter the dusk came early and darkness settled by four-thirty. It was a quieter time before security cameras and the glare of overzealous outdoor lights, when the evening still felt natural, unbothered, and kind to the living world.

Those towering privet hedges, fifteen feet tall or more, defined the Hamptons estate section. Later, as a young gardener, I would prune those same hedges under the June sun, their small white flowers perfuming the air with a sweetness that rivaled my mother Dyan’s favorite, Lily of the Valley.

The memory now feels like a parable, a young caretaker inhaling both fuel and beauty, unknowingly rehearsing the questions that would shape his future work: how we power our lives, and what it costs the natural world.

A few miles away, on my own street, Little Plains Road, another kind of wonder waited. Our neighbor was Larry Rivers, the celebrated Pop artist whose studio garage stood like a temple to creative disorder. On my walks or bike rides, I would steal what I called innocent peeks inside. Canvases leaned against walls, drawings filled with human gestures and bold movement covered the space.

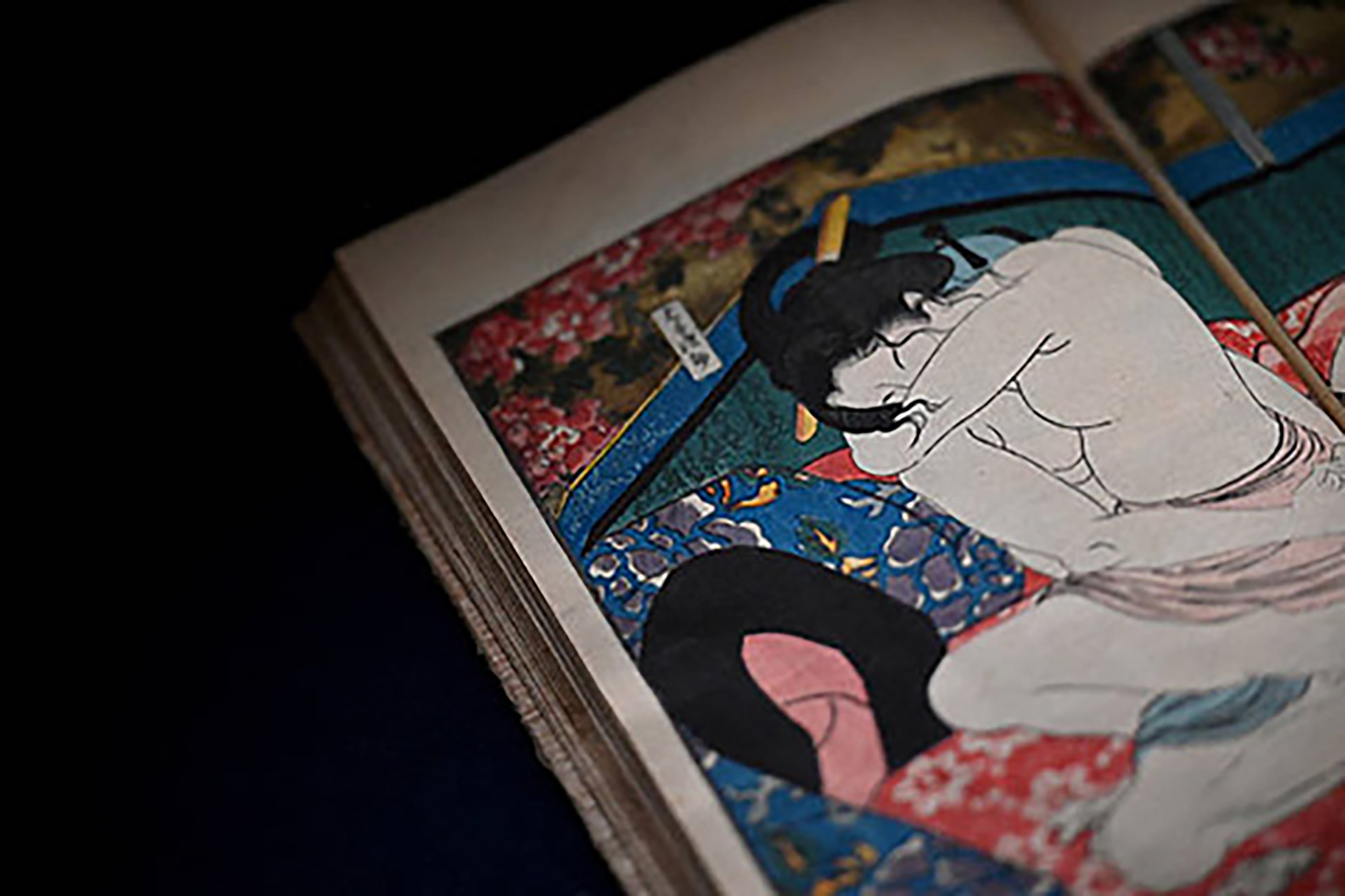

Some reminded me of the Japanese shunga and Chinese erotic art I had first encountered in Charlotte’s library. The exaggerated forms and mythical sensuality of those works met the sharp, confident line of Rivers’ draftsmanship in my young imagination. Around that time, as adolescence unfolded, I began to feel a natural mix of curiosity, humor, and wonder about sexuality itself, how the body, like nature, could be both playful and profound. Those early years were filled with a kind of innocent silliness, an awakening that was as natural as it was confusing.

Looking back, I see how that combination, the shunga’s heightened fantasy, Rivers’ mastery of line, and my own restless energy, quietly shaped my devotion to drawing. The honesty of those images stirred something real in me, connecting desire and art, imagination and empathy. It was, in its own way, another form of seeing.

Rivers, known for blending intimacy, wit, and rebellion, often used sensuality to explore the ties between the personal and the cultural. Those early impressions, mythic shunga, masterful linework, and the hum of creative risk became part of my natural education, guiding how I draw, observe, and care.

“Life delivers its teachings freely, in birdsong, in brushstrokes, in the hum of a car engine, or the flicker of a wing at dawn”

Those moments, looking into the Cords’ library and later the Rivers’ studio, taught me something that has stayed with me ever since. There are no coincidences, only lessons that appear when we are open enough to see them.

That same awareness guides me now. I turn off my porch light at night, not even on a sensor. The darkness feels calmer, and I have come to learn it may even be safer. Studies show that leaving a porch light on all night can make it easier for thieves to see what they are doing. The same light that disorients migrating birds can also make human life more vulnerable.

Between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m., especially from August through November, unnecessary outdoor lighting throws migrating birds off course. It draws them toward buildings where confusion and exhaustion take hold. Shielded lights, drawn curtains, and motion sensors all make a difference, but sometimes the simplest step is to let the dark exist as it is.

Anyone who has ever found a bird stunned beneath a window, or heard that soft, unmistakable sound against the glass, knows the feeling. Turning off a light becomes a quiet act of protection, for them, for us, and for the world we share.

So tonight, and through these migratory weeks, I will keep my porch light off and let the sky take over.

Sometimes the simplest act of love is to trust the night itself.

Explore the growing space of Green Religion where stories connect us, creativity leads to awareness, and climate justice remains at the core.

We value your privacy. Your email address and personal information will be used solely for sending updates from Green Religion. We do not share your information with outside parties, and you can unsubscribe at any time.