First Meanings

Our first encounters with the color green, as something specific, often arrive through childhood stories and songs. For some, it’s Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham, the insistence that something strange and unappetizing might turn out to be delightful. For others, it’s Kermit the Frog’s plaintive ballad, It’s Not Easy Being Green, where he laments being overlooked, only to realize that green carries its own quiet strength. Traffic lights teach us early: green means go. Additionally, this light has become a verb in that we “green-light” things. “To green” is now a verb.

It’s Not Easy Being Green: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=51BQfPeSK8k

Our relationship with green is in our bones. Our primate ancestors evolved in forested or jungle environments, where the ability to distinguish shades of green could mean finding food, avoiding predators, or spotting ripe fruit against the verdant foliage. On much of the planet, the first green of spring signals the upcoming ending of winter. The small buds that seem to appear out of nowhere push the dirt aside as they reach toward the life-giving sun, photosynthesis on display.

The Green Giant (1960s): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R0LurEEv0lM

The Green Giant (1980s): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OUxNs4FZHcQ

This has been captured by Robert Frost in his poem Nothing Gold Can Stay, a well-known meditation on the pale, silvery green shoots and buds that appear after the dormancy of winter.

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

Green Inequities, Green Longings

Studies have shown that in many cities, access to parks, trees, and clean air is divided along economic and racial lines. Decades of redlining and disinvestment, however, left many minority and low-income neighborhoods without adequate green infrastructure, exposing residents to higher levels of pollution, heat, and stress.

Research shows that limited access to green space correlates with higher rates of anxiety, depression, obesity, heart disease, and even premature death. A large European study estimated that thousands of lives could be saved annually if cities met the World Health Organization’s recommendations for green space. Greening cools the urban concrete canyons, reducing the urban heat island effect, where built environments trap dangerous levels of heat and pollution. It makes sense that Forest Bathing has become a thing, let alone popular. It could also be called “hiking.”When green is added to underserved neighborhoods, a paradox often follows. New parks and plantings can drive up property values, fueling what scholars refer to as the Green Gentrification Cycle. Sometimes gentrification precedes greening, sometimes it follows, and sometimes both reinforce each other in a loop. What begins as an environmental justice initiative risks displacing the very residents it intended to serve.

Green Acres: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTcPFJqbcJc

Beyond policy and sociology, green’s meanings have long stretched across cultures. In ancient Egypt, Osiris, the god of fertility and the underworld, was depicted with green skin, symbolizing both renewal and decay. In Islamic tradition, green is a sacred color linked with paradise. Across Africa, it appears on flags as a sign of natural wealth. Taoists used jade in rituals of immortality, believing it could preserve the body after death.

The eye, too, privileges green. Our vision is most sensitive to wavelengths between 520 and 565 nanometers, a legacy of primate ancestors who relied on distinguishing subtle shades in the forest canopy. Today, hospitals, schools, and workplaces use green because it soothes the nervous system. Night-vision technology is tuned to green because our eyes detect it most effectively.

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (born 1742, Germany, died 1786, Sweden) was a German Swedish chemist who independently discovered oxygen, chlorine, and manganese. In 1775, he discovered a brilliant pigment he named Scheele’s Green. It was wildly popular due to its vibrant color and single-pigment composition. He reportedly wrote to a friend the year before the color was introduced, expressing concern that users should be informed about its poisonous nature. “But what’s a little arsenic when you’ve got a great new color to sell?”

One evening in 1864 at the Paris Opera, Empress Eugénie appeared in a gown of such radiant green that it was celebrated in the next day’s papers. The shade soon christened Paris Green, or Scheele’s Green, quickly became the height of fashion on garments and in drawing rooms before making its way to Victorian England.

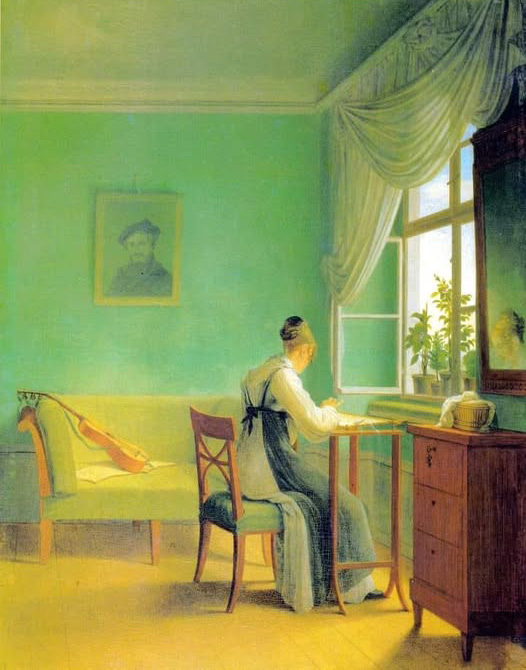

During the Industrial Revolution, in smog-covered streets, Victorians longing for rural life favored cloth reproductions of fresh flowers since the bloom is fleeting. This reflected a growing interest in preserving green urban spaces. Many of London’s iconic gardens originated in this period. The color was used in paints, wallpapers, textiles, artificial flowers, and even children’s toys, often containing toxic pigments.

At that time, artificial flower makers who worked with arsenic greens often fell ill or died, with open sores on their hands. William Morris, a leader of the Arts and Crafts movement and heir to a copper mine, dismissed the dangers as “humbug,” even while his wallpapers and textiles were colored with arsenic-based pigments. In the 1870s, however, Morris switched to arsenic-free greens due to public pressure, though he believed his arsenic wallpaper was harmless since no one in his home fell ill. Despite this belief, arsenic was widespread, used in food and dyes.

The pigment’s reach was so extensive that it was alleged to have hastened Napoleon’s death during his exile, seeping from green wallpaper in his chambers of confinement.

Poison, Culture, and The Green Horizon

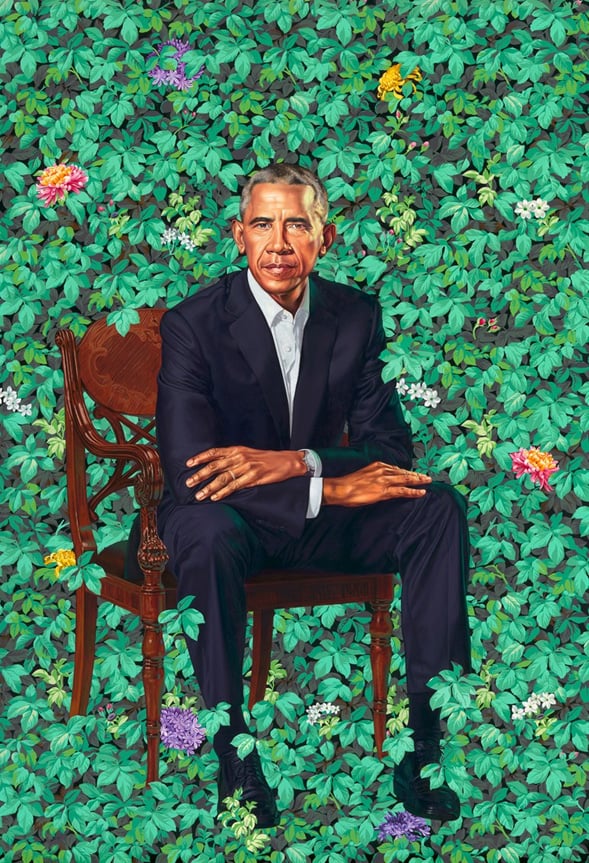

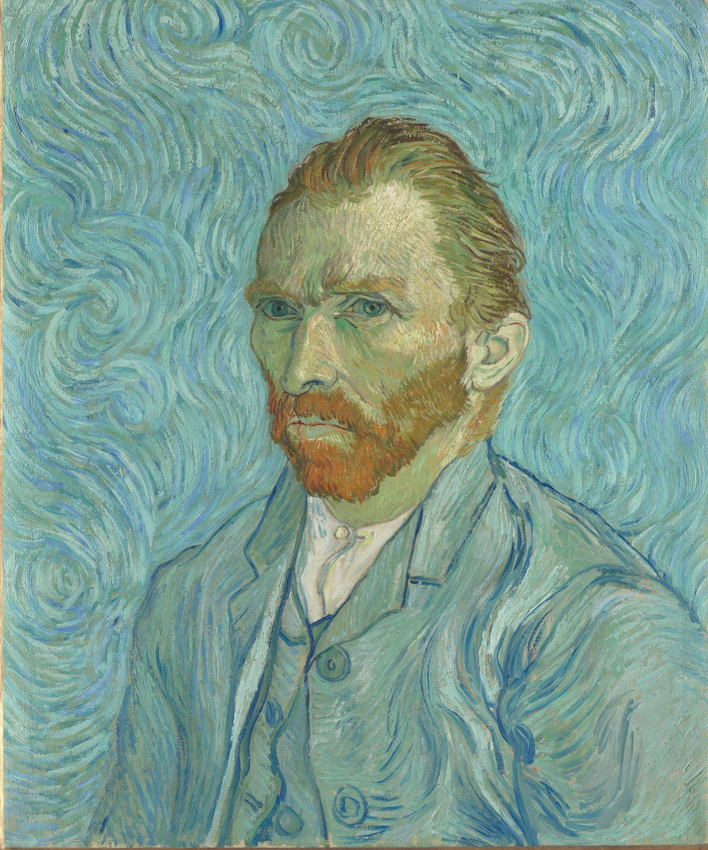

Emerald Green, a cousin of Scheele’s Green, found its way into the paintings of Monet, Van Gogh, and Gauguin. It was as toxic as it was vivid, used not only in paintings but even in confections and insecticides. One can consider how this must have affected Van Gogh’s mental health and, ultimately, the story around his death.

In addition to using the toxic pigment, the artist was known to frequently drink “the green fairy,” absinthe, made with Artemisia Absinthium, or wormwood. Historically, it has been considered poisonous. This is due to its high alcohol content, rather than the presence of thujone, a neurotoxin found in wormwood.

According to the Bible, wormwood wasn’t a medicine, but a plant that represented intense bitterness, punishment, and spiritual decay. It was used as a metaphor to describe God’s judgment for sin, the harsh consequences of immorality and injustice, and the hardships of life.

Originally formulated in Switzerland, absinthe held its greatest popularity in 19th-century France. Between 1875 and 1913, French consumption of this liquor increased 15-fold. It became an icon of “la vie de bohème,” and in fin-de-siècle Paris, l’heure verte (the green [cocktail] hour) was a daily event.

Starting in the late 1850s, absinthe gained medical interest and was used in animal experiments with either the liqueur or wormwood oil. A distinct condition—absinthism—emerged alongside the early descriptions of alcoholism and was associated with gastrointestinal problems, sudden hallucinations, epilepsy, brain damage, and psychiatric issues. We now know alcohol was the true cause.

French scientific warnings eventually made their way into popular media. They were met with denial from a government focused on tax revenue and an industry profiting from sales. Meanwhile, people from all walks of life convinced themselves that the dangers were at least balanced out by the pleasures of absinthe’s ritual and its mistaken reputation as an aphrodisiac.

In 2020, a study published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) concluded that it was not medically possible for Van Gogh to have shot himself at the angle reported without suffering powder burns, reinforcing theories that the shooting was accidental — and that he may have protected the teenage René Secrétan from investigation.

“I should like to do portraits which will appear as revelations to people in a hundred years… using our modern knowledge and appreciation of colour as a means of exalting character.”

Green has always carried cultural weight. It can be idyllic, as in Green Acres or The Green Green Grass of Home. It can signal envy, as in “green with envy,” or abundance, as in the smiling Green Giant of 20th-century advertising. It surfaces in pop music, from Tom Jones to J Balvin. Each iteration adds a layer to our collective sense of what green means — oscillating between nature, jealousy, pallor, and cash.

Tom Jones, The Green Green Grass of Home: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j64H2aWWU0E

In 2017, Pantone named Greenery its color of the year. Yet even today, many industrial green pigments contain harmful chemicals such as chlorine or cobalt. Our obsession with “natural” green persists, but so do its contradictions. Greenwashing remains common, selling products marketed as eco-friendly that conceal toxic processes or materials.

At the same time, research continues to emphasize the importance of genuine greenery. A Harvard study tracking thousands of women over eight years found that those living near more vegetation had a 12% lower mortality rate. Green surroundings improve mental health, boost physical activity, and reduce exposure to air pollution. Urban forests, community gardens, and green rooftops are no longer luxuries; they are lifelines in a warming world. We have been determined to pave paradise and put up a parking lot — to our own detriment.

Our ancestors depended on greenery for survival — food, shelter, and medicine. Today, the stakes are higher. Climate change, deforestation, and pollution threaten the ecosystems we rely on for air, water, and balance. The color green reminds us not only of beauty but of fragility.

Yet the story of Scheele’s Green has fascinated writers across decades, symbolizing our worst consumerist tendencies: our urge to follow every trend, even when harmful, and our tendency to imitate nature rather than care for it.

J Balvin — “Verde”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DAlvSNHny2s&list=RDDAlvSNHny2s&start_radio=1

Our ancestors depended on greenery to survive. Today, the stakes are even higher. Climate change, deforestation, and pollution threaten the green spaces we instinctively turn to for calm and connection. In a world growing hotter, grayer, and faster, choosing green isn’t only a design decision — it affects our health.

In an increasingly artificial world, choosing truly sustainable practices goes beyond aesthetics. It is about justice, survival, and resilience. Authentic sustainability may be challenging — but it may also be our only viable path forward.

Explore the growing space of Green Religion where stories connect us, creativity leads to awareness, and climate justice remains at the core.

We value your privacy. Your email address and personal information will be used solely for sending updates from Green Religion. We do not share your information with outside parties, and you can unsubscribe at any time.