What Happens When Ancestry Becomes Architecture?

Sterling Rook (b. 1984, Miami) makes artwork that is informed by both the culture and the ecology of South Florida and its persistent development. He is a graduate of Florida International University’s MFA program and a resident at the Bakehouse Art Complex. Whether through his neighborhood-mapping mural, Bass Famous Tabernacle or his sculptural use of palm fronds, Rook returns to the intersection of the seemingly disparate cultures of his heritage: South American and Caucasian via the British Isles. His work is particularly significant to Miami yet plumbs history for the universal language of pattern.

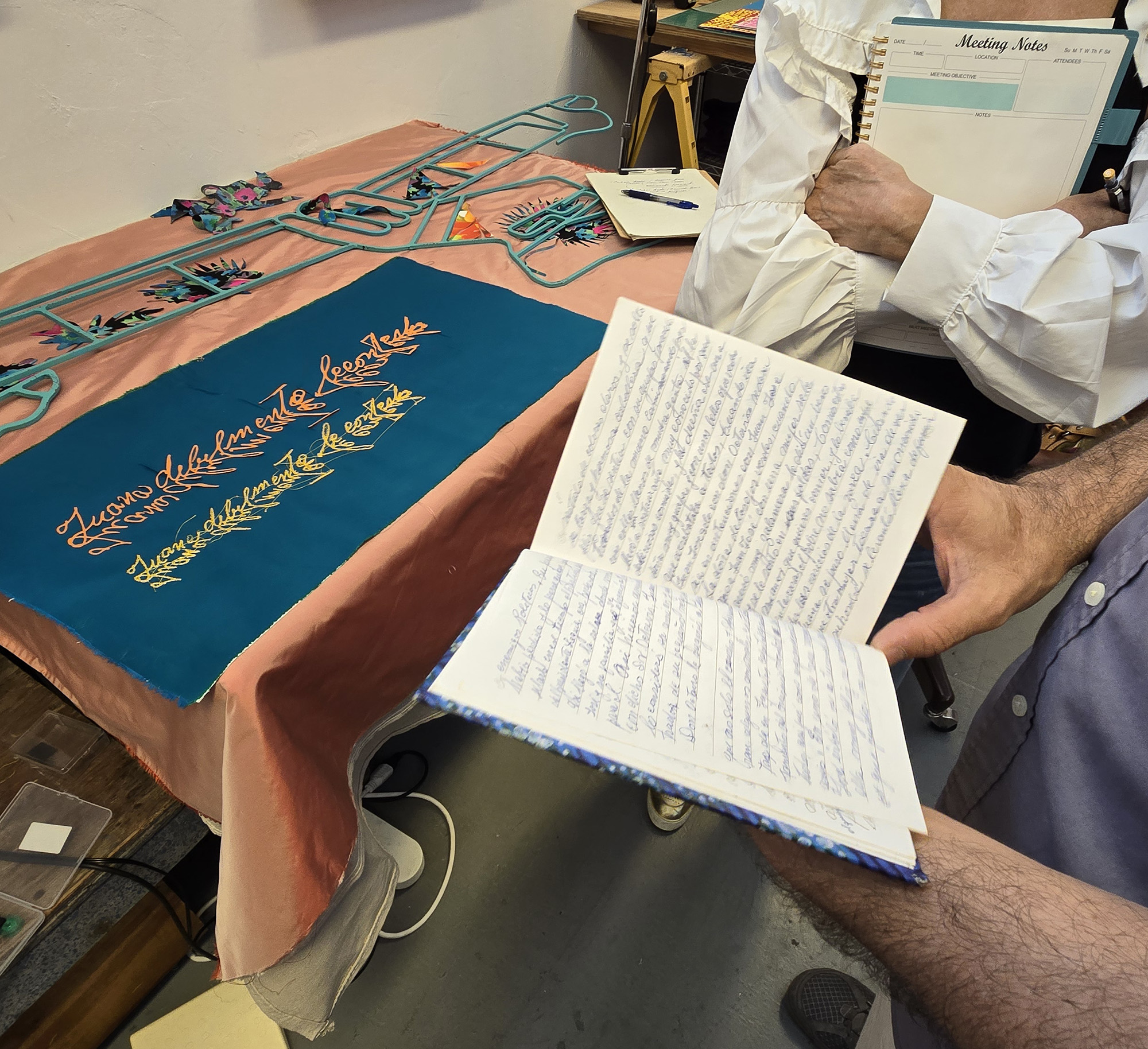

Artists inhabit their own intellectual worlds, rich oceans of self-crafted information, influence, and priorities. The materials they choose, the histories they trace, and the influences that shape their vision form a tapestry of origins. For Rook, art becomes a means of contemplating the double helix of his identity: the entwined DNA of his Peruvian and British heritage. His work emerges from that genetic duality, translating inherited traditions of handicraft and pattern into contemporary reflections on place, ecology, and ancestry.

Rook’s Peruvian grandmother, a ‘reweaver’ who restored fabrics, and his grandfather, a tailor, reflect this tradition. On his British side, his ancestors were rope makers, and their occupational surname, Stringer, highlights this craft. Across these lineages, a common theme emerges: the transformation of flexible fibers into resilient forms. Both rope and tapestry depend on countless small actions, the intertwining of individual strands into a cohesive, flexible, yet durable material while following a pattern.

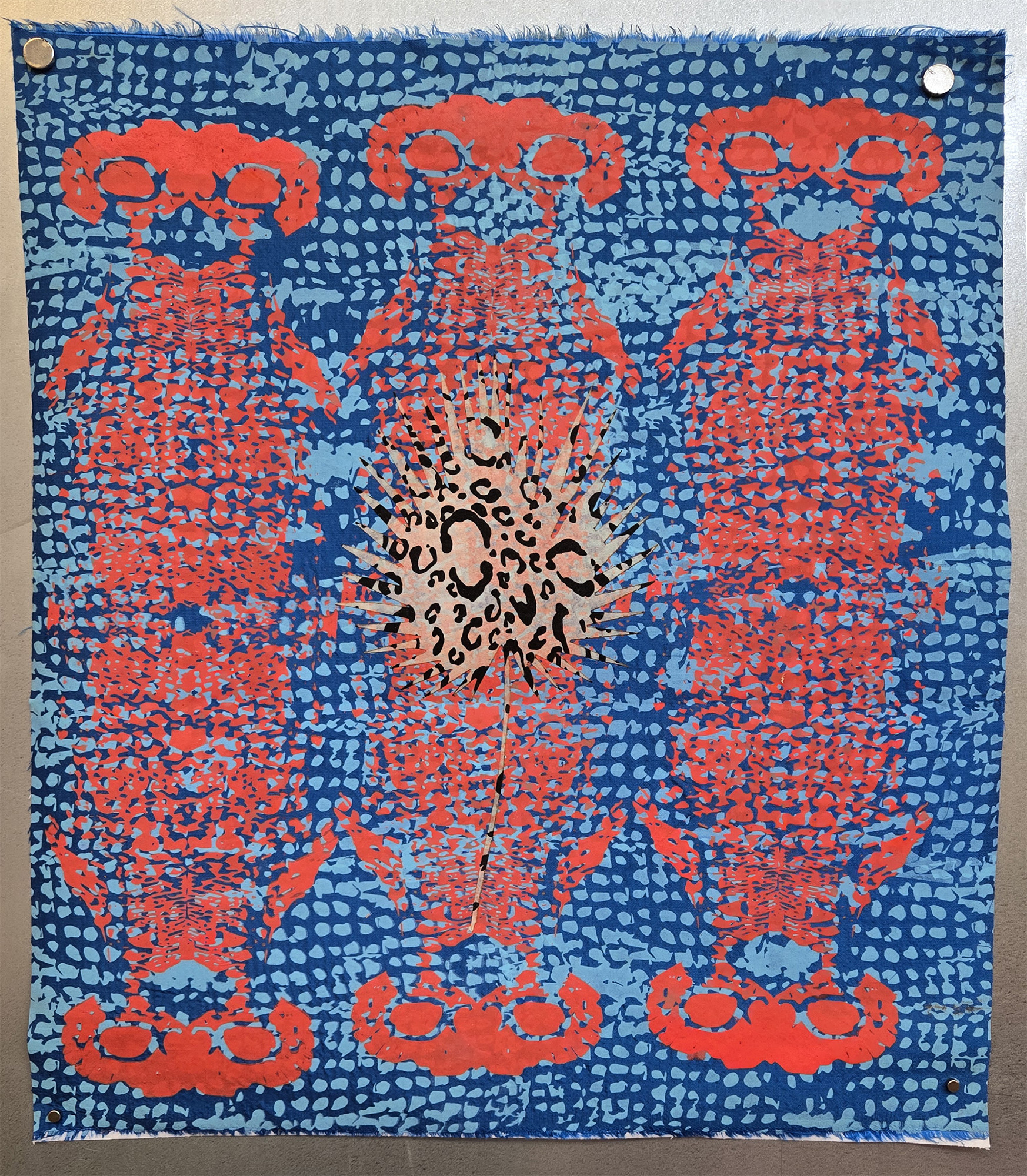

Currently, Rook is working with fabric, layering stenciled imagery to create visual palimpsests. These pieces, usually around 12 x 16 inches or thereabouts, are but simple rectangles containing multivalent complexity. They each have a background or base pattern, a central icon, and then decorative yet informational imagery or patterns, each colored with jewel-like intensity.

These works demonstrate a connection to pre-Columbian aesthetics, absurdly defined as anything that existed in the Americas prior to the arrival of Columbus in 1492. He parallels this with the Book of Kells, the illuminated manuscript created by Irish or Scottish monks around 800 A.D. In both, he finds a devotion to color, pattern, and geometry, a shared understanding that repetition can be a form of reverence.

Rook pairs the saturated colors of Latin America with the intricate ornamentation of medieval scriptoria. Geography is transcended by Sacred Geometry, the study of geometric shapes, patterns, and proportions believed to contain spiritual significance in various religious and philosophical traditions. The Golden Ratio, mandala patterns, and Platonic solids contain these spatial relations. They appear across cultures and centuries and are evidence of a shared human intuition, as well as the recognition that nature itself is patterned. There is nothing in nature that does not contain this proposition.

Making as Worship

His approach is aesthetically and intuitively based, taking what resonates from the visual history of cultures, and leaving the rest. These structures are not simply motifs; they are metaphors for interconnectedness. Rook finds in universal rhythms the accumulation of the small to express something larger, a reflection of both community and quantum physics.

“I want to make my own religion,” he states, and “When cultures intersect, gods mutate.” Through the selection and reinterpretation of imagery across traditions, this syncretic urge reflects the hybrid nature of Miami itself, a city shaped by migration and mythologies. His interest in pre-Columbian deities, Celtic knots, and Buddhist Dzogchen philosophy forms a cosmology that is less about belief than about attention. Like the monks of ancient scriptoria, Rook treats pattern as a form of devotion. The act of painting or weaving becomes a way to honor ancestral modalities of the world, to reassert the sacredness of nature in an age of consumption.

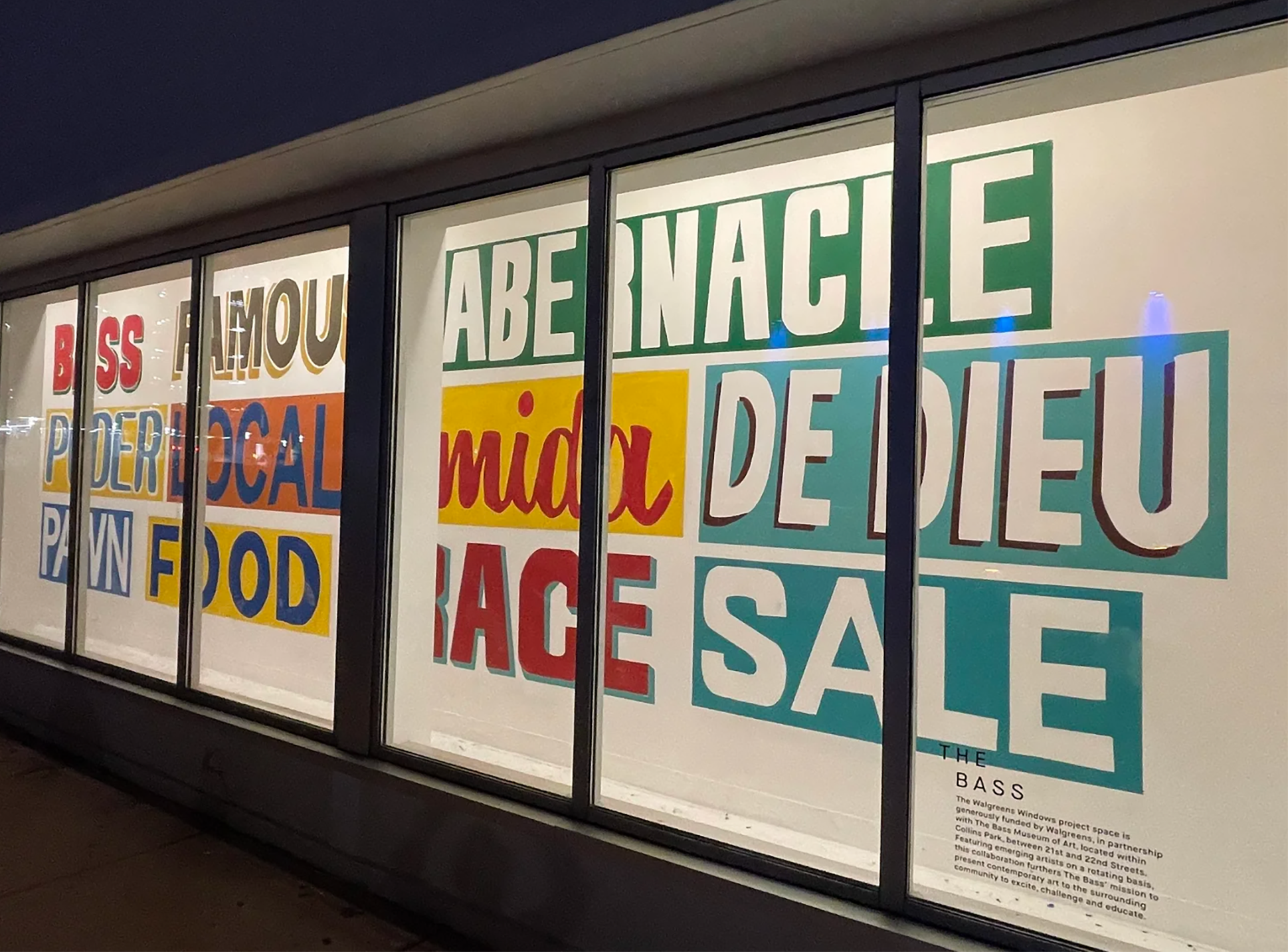

In his Bass Famous Tabernacle from 2021, a large-scale mural that transformed cartography into liturgy, he gathers the names of Miami neighborhoods’ landmarks from Allapattah, Little River, Liberty City, Opa-Locka, and Hialeah. The stacked, rhythmic letters turn typography into a chant of place. Each of these neighborhoods is currently experiencing a boom of development and will soon have a very different face. The mural is less about literal geography than about what it feels like to inhabit a place, with all its tensions, affinities, and histories combined with the three languages of Miami: Creole Haitian, Español, and English.

Rook has watched the streets of Miami become tame, their edges sandblasted by development. Through the repetition of language in Bass Famous Tabernacle, he creates a visual litany that resists erasure. The mural’s layering transforms the city’s linguistic landscape into a collective prayer for remembrance. The poetry of names has become commodified, and in an era when the city’s neighborhoods are rapidly gentrifying, the mural is both a celebration and a protest.

Rook draws upon the traditions of text in art, from Glenn Ligon’s stenciled phrases to Lawrence Weiner’s conceptual typography. His mural insists on the specificity of Miami, and the names he inscribes become both intimate and monumental, asserting that community identity deserves public recognition and is a public declaration that these places, and the people who built them, matter.

In his Almost Home sculpture, Rook used a material that is linked to Miami’s landscape: the palm tree. Rare is a Floridian image without this symbol. It reads as “vacation,” “easy living,” or even escape. They are the stuff of dreams of a better life, ease, and comfort. Their fronds are everywhere: scattered across streets after storms, making shade from the hot sun, an endless supply of landscaping employment.

The palm is Miami’s memory, always shedding, always alive

Rook made interactive structures with rebar, a familiar sight to any Miamian, and the leaves of the palm tree. These sculptures elevate the palm from background to protagonist and address their symbolic weight. They are sacred branches in Christianity, signifying rebirth and triumph, and are the means of shelter in the Caribbean and Latin America. In transforming them into art, Rook brings attention to their dual nature: fragile yet enduring. The palm frond becomes a metaphor for Miami itself, a city that continually sheds and renews, oscillating between glamour and decay, growth and loss, feast and famine. His faded greens are sun-bleached and carry the patina of the tropics, the color of time made visible. Rook’s pinks, importantly, are the slightly gray, vintage shades of tropical nostalgia.

They may also be used successfully in ropemaking.

His gesture is ecological as well as aesthetic: what is deemed disposable can be revered. By recontextualizing the frond, he restores it from detritus to sacred status, aligning himself with ancient nature worship. This understanding of Sacred Geometry is found in Peruvian textiles and pre-Columbian art, among others.

Rook’s palm frond sculptures are in a lineage of artists who utilize overlooked materials into carriers of cultural and environmental meaning. Ana Mendieta embedded her body in the earth and leaves to root her identity in the landscape. Like Mendieta, Rook makes the natural world inseparable from questions of being and belonging. Eva Hesse embraced fragile and ephemeral materials, turning impermanence into conceptual strength. Rook similarly embraces fragility, allowing the frond’s short lifespan to speak of the unavoidability of the cycle of life. El Anatsui uses discarded bottle caps in monumental tapestries that address consumption and memory. Rook transmutes fallen fronds into objects that collectively carry the weight of ecological and communal history. Faith Ringgold and Sheila Hicks expanded textile traditions into forms that tell stories. Rook’s palm fronds echo this trajectory, translating fiber into a tropical, Miami-specific idiom and linking to his dual inheritance.

His work posits that culture and environment are entwined. Just as Bass Famous Tabernacle maps the lived geography of neighborhoods, his palm frond works map the fragile ecologies of place, and his fabric works gather imagery that proves to be universal. Through these materials and motifs, Rook bridges the visible and the invisible, the social and the sacred. His practice draws upon ancestral knowledge, reminding us that the stories we tell matter, be it in rope, fabric, or palm.

Sterling Rook’s work reclaims nature worship and sacred geometry as contemporary tools of understanding. Each pattern, each frond, each word painted on a wall becomes a form of prayer through attention and care. He questions whether the cultures of Peru and Great Britain are so disparate.

His work reminds us that making art is a form of listening.

Explore the growing space of Green Religion where stories connect us, creativity leads to awareness, and climate justice remains at the core.

We value your privacy. Your email address and personal information will be used solely for sending updates from Green Religion. We do not share your information with outside parties, and you can unsubscribe at any time.