As I prepared to profile our first artists for the public launch of Green Religion, the late self-taught wunderkind Henri Rousseau naturally came to mind. This story, however, begins not with Rousseau but with my meeting a young Costa Rican artist, cook, nature tour guide, and lover of all things verdant—Ismael Espinoza. Ismael, a ‘Tico’ (Costa Rican native), lives in Manuel Antonio along the Pacific coast and is one of our inaugural featured eco-conscious makers. In the lushness of Costa Rica’s coastal hills, I found a unique opportunity to relate to this young man’s budding, self-taught artistic journey in a way that echoes Rousseau’s own.

I met Ismael during one of my three visits to Costa Rica in the spring and summer of 2024. My first experience breathing the air upon exiting the airport in San José, the capital, was life-changing. The air felt incredibly clean, fresh, and almost “greenish,” filling my lungs with a soft, rejuvenating tone.

Earlier in the spring, I once again found myself in beautiful Manuel Antonio, after my first visit back in early 2021. Ismael was working at my go-to boutique hotel, serving breakfast in the morning at the small hillside café and pool area. Our quiet morning chats always began with the loud calls of the local Howler monkeys, whose deep calls resonate through the high green canopy overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Howler monkeys are considered the loudest land animals in the New World.

As an early riser, I would sit on my balcony around 5:30 AM and watch hotel staff as they appeared, stepping down the winding stone paths in the soft morning light, surrounded by the intimacy of perched hillside rooms. The air was filled with the soft murmur of bird songs, mingling with the squawks of red scarlet macaws flying across the flawless blue sky. I noticed a young man making his way down to the café area. There was something about him that signaled peace, as if he were a high-flying seabird gliding serenely through the air.

While having breakfast, I observed his naturally toned physique. His strong, smooth legs—lightly tanned and subtly muscular—spoke of a life of agility and survival. They didn’t suggest the frantic walks of someone navigating city streets or the overworked muscles of a gym-goer. With my keen eye and photographic memory, I made this conclusion quietly to myself.

This tranquil, fit, and agile man seemed to move through nature as part of it. I watched as he prowled the patio pool area like a jaguar, his attention drawn to the plants around him. I saw him rescue a passion flower bud that had fallen behind the masonry wall of the poolside patio. He was determined to bring the hidden buds into full sunlight. The next morning, I witnessed a small miracle: the flower he had nurtured was now glowing in full bloom, its resilience evident.

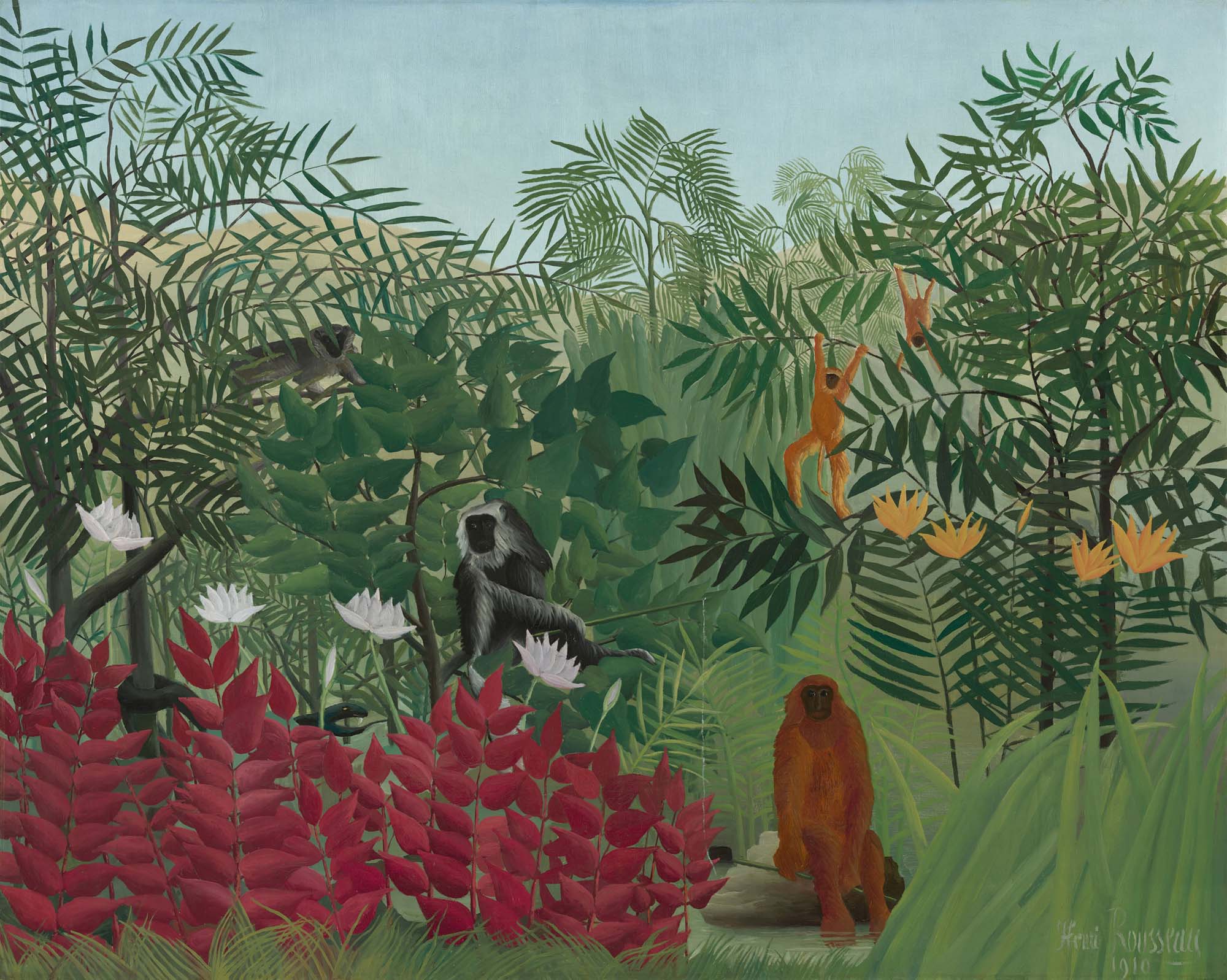

Like the late painter Rousseau, I learned that Ismael’s journey as a visual artist had unfolded with an intuitive rhythm. Both he and Rousseau—each speaking only in his native tongue—were guided by a deep love for nature, a theme that echoed throughout my encounter with Ismael. Who among us has not longed to escape the monotonous routines of daily life? Rousseau, after all, never left Paris but dreamt of lush jungles filled with rustling palms, howling monkeys, and vibrant toucans soaring above. Perhaps that same yearning for a deeper connection with nature lives on in Ismael. His art captures a piece of that dream, lived fully in Costa Rica and shared with everyone he meets, including the plants and animals that surround him.

Over the course of my five-day visit, my communication with Ismael blossomed. Our first attempts to speak were clumsy, but in time, our language barriers became a gift. It was a reminder that communication isn’t just about words; it’s about connection. We found common ground in shared smiles, gestures, and photos. We both opened our mobile phones to share images of nature, and when Ismael scrolled through his photos, I noticed some of his artwork. He had been creating small paintings of plants, capturing their textures without worrying about perfecting perspective. Intrigued, I complimented him enthusiastically. I take pride in inspiring others’ creative ambition—a feeling that is both selfish and instinctively healing.

The next day, on his day off, I offered to show Ismael some of my drawing and painting techniques on my hotel balcony. During my repeat visits to the Pacific coast, I often set up a small drawing and watercolor station on the breakfast table. Ismael arrived just as the sun began its fiery golden descent over the westward horizon. To pique his interest, I introduced him to the work of Henri Rousseau. Like Rousseau, Ismael is deeply connected to nature. Nestled in the coastal jungle hills, Manuel Antonio overlooks Isla del Coco, a view so dreamlike it could easily have inspired Rousseau’s fantastical visions. Isla del Coco was even depicted in the opening sequence of Jurassic Park (1993).

We stood together, admiring Rousseau’s work. I shared insights into his technique: how the artist layered colors, starting with a dark base, and gradually adding lighter layers to create depth. Rousseau’s paintings, rich in detail and dreamlike in quality, reflected a longing for the simplicity of nature, a contrast to the chaos of urban life. Ismael’s eyes lit up with fascination, and I sensed a kindred spirit forming between him and Rousseau. Our shared love for nature and art-making became the common thread between us.

Summer visit number 2. 2024

My second trip in July marked a shift toward more independence. I rented an Airbnb halfway between Quepos and Manuel Antonio. Quepos is a charming coastal town with lots of shoreline and signature ecosystems. Deep-sea fishing is a popular tourist attraction in the area. While many in the higher elevations of Manuel Antonio take pride in the panoramic ocean views from their hillside homes, with sunsets so beautiful they seem almost unreal, I can only relate through the teasing photos in luxury travel magazines.

Ismael and I reconnected, as he knew I was returning. This time, I was to visit his neighborhood and apartment. I had seen much of his surroundings during video calls. Video chats were a rarity for me, but these virtual moments made me realize how much of my art-making practice is solitary. Yet, during our calls, we always related to “the grand green canopy of life,” which assured me that I was never truly alone.

I arrived at Ismael’s apartment after a five-minute cab ride along narrow jungle roads. His home, part of a modest, stacked complex of painted buildings with corrugated metal roofs, bore the marks of life well-lived. His apartment, or “space,” was ground-level at the end of a narrow driveway. A large sliding grass-green steel door with a locked chain beckoned visitors. Outside, a lovingly arranged collection of plastic potted plants sat on old, weathered chairs, thriving in the tropical air. The plants, celebrated more for their green leaves than their occasional flowers, were all co-owners of the lush environment. Ismael referred to them as “his babies,” reflecting the deep affection that many Costa Ricans feel for their sacred land. He also expressed his dislike for the plastic pots but found solace in knowing that they were being recycled—or as we now say, “upcycled.”

Inside, the simplicity of his home felt a bit too warm for me, as there was no air conditioning, and the plumbing didn’t offer hot water. The space was small and humble, with a PVC pipe serving as the kitchen sink faucet, no glass in the windows, and only bars to let in the breeze—and sometimes raindrops. But the room was immediately filled with Ismael’s love for life. There was a calm that invited pause. He eagerly showed me his 10-gallon fish tank, displaying his prized freshwater fish with childlike excitement. Serenity entered the room.

As rain began to fall outside, spattering against the driveway inches from the big green door, Ismael tidied up his “cocina” (kitchen). While I rested on his single bed, I pulled the coverlet over me and realized it was damp—though not enough to cause discomfort. I quickly reasoned with it. The sound of raindrops on the corrugated tin roof, distant dog barks, and the crowing of roosters lulled me to sleep. After about 20 minutes, I stepped through the two curtains separating the kitchen from the bedroom—one yellow, one green. The fish tank glowed happily under the soft light of its aquarium lamp. Exposed incandescent bulbs overhead gave a warm glow. Cute little fish swam back and forth in the tank, and the green aquatic plants swayed gently. Ismael shared his deep affection for home aquariums, and he also tended to a few others in the surrounding hills, many of the fish gifts from clients.

We sat down to a simple meal—toast made from leftover bread Ismael always rescued from the hotel kitchen. We laughed over the meal, admiring small artworks on paper that Ismael eagerly presented—intuitive landscapes and leafy drawings, dabbed with color, mostly shades of green. They burst with the eccentric awkwardness that defines the best Outsider art.

Then came the heart-tug. At the hotel the next morning, at breakfast, Ismael asked if I liked his apartment. For the first time, I saw him appear timid—a sensitivity I had not noticed before. I wondered if he felt insecure about his living situation. He knew I shared his deep connection to the environment, a mutual muse that bonded us. In an instant, my eyes lit up, dispelling the sadness that had clouded my face just moments before. I used Google Translate to express my feelings as best I could: “I can only wish I were the fortunate man living in the most beautiful ‘garden house’ I have ever stepped into. I am extremely envious.” I will always remember that moment, especially the way his infectious smile seemed to shine even brighter in the Costa Rican morning sun.

Where was Ismael from? Where was he born?

Ismael shared that he was adopted shortly after birth. His adopted parents raised him in a small home nestled in the hillsides of Grifo Alto, a charming district high in the mountains of Puriscal Canton, Costa Rica. Puriscal is about a 40-minute drive from San José, the capital, in the country’s Central region.

Our friendship unfolded naturally. I reached out to Ismael from Miami via mobile chats, saying, “I would love to visit Puriscal and the mountains!” Knowing that this area would be a first for me, I suggested we meet at the San José Airport and drive together to his hometown region. Why not? By then, I had come to appreciate Ismael’s gift as a nature guide—his ability to explore hidden, untouched places while respecting their delicate ecosystems. During my second trip to Costa Rica this summer, Ismael invited me on a magical trek to secluded Playa La Mancha, tucked between Quepos and Manuel Antonio. This beach, with no direct road access, is the definition of seclusion. The final descent was a rocky, tricky path that opened to a hidden cove—a challenge well worth the reward. The water was perfect, the sand soft, and time seemed to stand still. That excursion felt as effortless as most things in Costa Rica.

Soon after, it was time for Ismael to take flight. I decided to organize the trip to Puriscal to explore his childhood grounds. At 33 years old, Ismael had never flown before, so I suggested he take his first flight on me. He would take a 20-minute flight from Quepos to San José, and my flight from Miami would land just an hour or two later. It seemed like a fitting adventure.

I landed in San José just after 1 PM on a mid-September day, breezed through customs, and exited the familiar airport to the sound of shouting taxi drivers. As I’d informed him, Ismael was easy to spot. He had flown Sansa Airlines, the regional airline where locals fly at half price—smile! Its small terminal is just five minutes from the main Juan Santamaría International Airport (SJO) terminal. “How was your first flight, Ismael?” I asked. He grinned, wiping sweat from his forehead and shaking his arms in excitement. I could not help but laugh—he was a new man, thrilled to have flown over and seen his beautiful country from the skies.

We jumped into our rental car, and within ten minutes, the misty air revealed the big green mountains ahead. I had to rely on Waze, Costa Rica’s favored navigation app, to guide me. Our Airbnb was in the Puriscal region, and I’d arranged it thoughtfully, knowing Ismael’s mother’s house was nearby. Ismael had mentioned that his mother’s home was small and could not accommodate visitors at the time, so I found us a spot in the Grifo Alto mountainous area. Both of us had checked the Airbnb’s map, and Ismael pointed out that the location was along the long mountain road he had grown up on.

Then, it started to rain—hard. As we ascended to the higher altitudes, I slowed down, letting the windshield wipers clear the heavy rain from my view. It was a road I did not know, but it was completely free of traffic. Growing up in New York, I’d learned to drive defensively, and now, more than ever, I was conscious of the remote surroundings. Ismael recognized the area from the photo our Airbnb host had shared. And sure enough, when we arrived at the gate, we honked, and it opened!

We parked in front of a gravel driveway that led to a multi-level home built with steel containers—a cool architectural choice. Our joyful host, Tatiana, a Costa Rican native, greeted us in perfect English, handing us an umbrella. She had mentioned in an earlier chat that she worked as a translator. With our luggage in tow, we carefully navigated the downpour to our flat, which was part of a steel container structure detached from the main house.

The flat felt private, and Tatiana handed us our keys along with a gift of freshly baked sourdough bread—such a thoughtful touch. The view from the deck was wonderful, though the mist from the rain soon faded into fog.

Then Ismael shared, “John, my mom is the next-door neighbor!” Things had already felt playfully surreal in this country, but this? This was one more delightful twist. We dried off and unpacked, taking in the sounds of rain and our mutual excitement.

By 5:30 PM, the storm had passed. We went to a nearby restaurant, and I was struck by how often people Ismael knew appeared in our path. He loved it. They loved it. I loved it. And it all felt so wonderfully right. Oh, and before we found our Airbnb, we stopped at a hillside restaurant, where Ismael knew a lovely lady working in the open-air kitchen. She greeted us with a hug and shared a delicious snack she had made in the open-fire oven. It was blissful and just what I needed in this new, enchanting place.

Exhausted I went to bed early. I slept soundly, though I woke around 4 AM to the sound of Ismael chatting in Spanish, softly on his phone with his mother. I remembered that he was an early riser. Our WhatsApp texts always arrived in the early morning, as Costa Rica is two hours ahead of Miami. He told me that, as a child, his father would catch the 4:30 AM bus into Puriscal for work, while his mother prepared breakfast and packed his lunch. That childhood routine had stayed with Ismael, ingraining an early morning rhythm that still shaped his days.

After I drifted back to sleep for another hour or so, I woke up and stepped onto the balcony. And then—wow! The fog I had thought I’d seen the day before? It was the rolling clouds of Costa Rica! As my eyes scanned the view, I realized I was surrounded by green mountains and rolling hills. It was breathtaking. I melted in gratitude.

What Was That Noise?

There were loud, primal yelling sounds echoing over the vast expanse of green mounds and distant, barely visible highlands. The flickering town lights in the distance still gleamed. A yelling of sorts, I thought. No, not dogs—what was it? As I was about to ask Ismael if it was a regional canine song I’d read about, he smiled and said, “Coyotes.” My eyes widened in agreement. I was frozen in place, but at peace, with a grin spreading across my face. The eerie yelps and yaps could be heard as far as my eyes could see, left to right. It lasted for a minute or so before a neighborhood dog and our host’s dog chimed in. It seemed they respected the familiar chorus of hysterics.

It is commonly thought that the howling of coyotes signals they’ve caught prey. But that’s not true. Why would they want to attract attention to their food? The wailing has many purposes. One is to call the pack together after individual hunts. Other times, it serves to communicate their presence to other packs, warning them to keep their distance from territorial boundaries.

The view cleared, and I realized what I’d perceived as fog the day before were actually the rolling clouds of Costa Rica! Ismael knew. I looked out, seeing nature in a whole new way. The expansive view of green mountains and rolling hills stretched before me, something so special about this place—and my first time experiencing it.

Ismael signaled that he was heading out through the big glass sliding door to visit his mother with kind purpose. A few minutes later, he called me, asking if I have had breakfast. Nope! He was back in five minutes, gifting the table with a warm plate of Gallo Pinto. Gallo Pinto is a traditional Central American dish consisting of rice and beans, cooked with garlic, oregano, onion, and bell peppers—essential to Nicaraguan and Costa Rican cultures. It’s served with breakfast, lunch, or dinner, and its comforting flavors connected me further to this rich culture.

Puriscal

Puriscal is a rural canton (district) in the Province of San José, Costa Rica, nestled in the northern foothills of the Talamanca Mountain Range, which divides the plains of the western Central Valley. Its capital, Santiago, was founded in 1868. Before colonization, Puriscal and its surrounding areas were the territory of the Huetar people, and Native communities continue to reside in the Indigenous territories of Zapatón and Quitirrisí. Despite its rugged terrain and fragile soils, Puriscal was long known as the granary of the Central Valley and San José, thanks to the abundant production of grains by a predominantly peasant population.

What excites both me and Ismael during our walks is the renewed attention being given to forgotten plant knowledge and the cultivation of respect for the many growing things in Costa Rica. Despite decades of land degradation, displacement of small farmers, and erosion of traditional knowledge, there are signs of potential recovery. The Costa Rican Institute of Rural Development (INDER) is committed to improving the quality of life in rural territories by respecting cultural identities.

Ecotourism plays a vital role in Costa Rica’s economy. The country is known for its ethical tourism, designed to respect and protect threatened natural areas and wildlife. With over 32 national parks, 25% of Costa Rica is protected land, making it one of the world’s top ecotourism destinations. The country encompasses diverse ecosystems, from volcanoes and beaches to cloud forests and wetlands, and offers a range of thrilling experiences within short distances.

Tourist No More

Costa Rica has become my second home—not just a place I visit but a source of inspiration that expands my vision for living, both in heart and mind. It now finds expression in my artmaking on canvas, paper, and beyond. Like Ismael and Henri Rousseau, we immerse ourselves in the gift of life, rooted in the rich soils around us, embracing every element of nature as part of this evolving philosophy we call Green Religion. It invites us to honor the land and explore how art can intuitively connect us to the rhythms of the earth.

In our next update, I will share more about my recent visits to Costa Rica and how Green Religion connects with the stories of others. I will tell you about Calling Ismael, where we delved into creating textile and assemblage art. Inspired by his self-taught crocheting—learned from YouTube videos—we collaborated to incorporate organic materials, gardening twine, recycled African glass beads, and upcycled found objects into our creations. This hands-on, intuitive process reflected the craft and environmental awareness guided by our very green inner compasses.

“There is so much more to come! Sign up for our bi-monthly newsletter and let us share our passion for connecting with kindred spirits through green stories directly with you.”

Copyright © Green Religion

Made with ♥ in Miami by Fulano

Quarterly, explore the growing space of Green Religion where stories connect us, creativity leads to awareness, and climate justice remains at the core.

We value your privacy. Your email address and personal information will be used solely for sending updates from Green Religion. We do not share your information with outside parties, and you can unsubscribe at any time.